Venture Capital needs to take a serious look into esports, or risk missing a once-in-a-generation opportunity

I’ve long believed that esports are an inevitable part of the future, and I wrote a four-part position paper discussing why the industry is currently at its inflection point. But it wasn’t until I read Scott Kupor’s book Secrets of Sandhill Road: Venture Capital and How to Get It that I realized it is the perfect industry for VC investment. As a side note, I highly recommend the book, which you can find here.

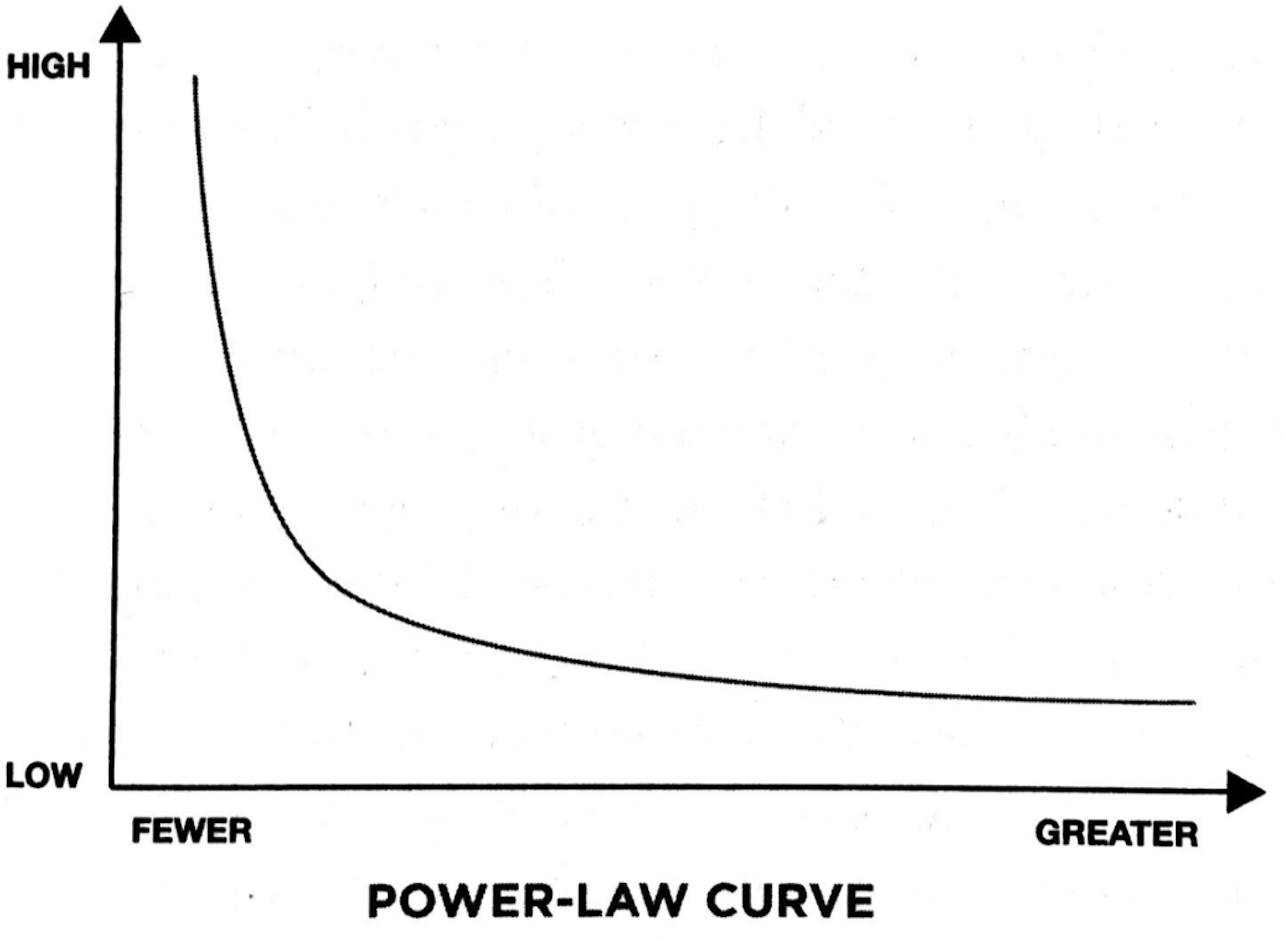

In his book, Scott describes the things that VCs look for in an investment. The two parts I want to talk about are what he calls the power-law curve and the VC investment criteria.

The power-law curve looks like this:

The basic theory behind the power-law curve is successful VCs don’t make their money off of a series of good returns but rather a few exceptionally great ones. Furthermore, the distribution of firms that invest in the companies that yield exceptional returns is non-normal and skewed. This results in a small percentage of firms capturing a large portion of returns to the industry.

Scott describes the most important characteristic to measure a VC as the “number of bats per home run.” That is, the number of investments per 10x or higher return.

In order to find the next home run, they look at three categories: people, product, and market. I will be focusing on market since the following will address an industry rather than a specific company.

Total Addressable Market

Finding the total addressable market for a nascent industry encompasses more than looking for the closest comparable and applying multiples. It requires some imagination.

Some may use traditional sports or video as the proxy for esport market size because it makes sense superficially. I believe the total addressable market is a melding of both, plus video games.

Like esports, traditional sports involve professional players competing for prizes and championships. Viewership is split between in-person experiences and online streaming/television, with the online portion making up the majority of viewers.

The market for video encompasses all prepared and live content consumed on a screen. The screen could be a TV, computer, phone, or tablet. The advent of streaming makes it possible to consume content live (ESPN) or on demand (ala Netflix).

What we think of as traditional gaming and traditional sports are slowly merging via video (streaming). Netflix’s CEO Reed Hastings has already said that Netflix consistently competes and loses to Fortnite, while athletes such as wide receiver Juju Smith-Schuster stream on Twitch and YouTube.

So what do we have now?

Gaming is already the largest form of entertainment by revenue, traditional sports markets are worth an excess of $100 billion, and the video industry (SVOD, streaming, etc) grows daily. Esports is capturing an ever-increasing proportion of the revenue from those three industries. The market is there.

Great, Who Do We Invest In?

I’ve written previously that I believe there are six total components of the future of esports, but only three potential investment vehicles:

- Distributors

- Teams

- Players

Right now the share of revenue in video games and esports is disproportionately allocated. The majority of revenue goes to game producers and distributors, with small amounts trickling down to teams, players, and content creators.

The main distributors of esport content are Twitch, YouTube, Douyu, and Huya. I am mostly familiar with the western esport scene so I will focus on Twitch and YouTube.

Twitch and YouTube are owned by larger parent companies (Amazon and Google respectively). I find it highly unlikely that there will be a disruptive distributor that reaches scale, so investing in distributors is likely not the right path.

I also believe it’s highly unlikely investing in an individual player will yield power law-type returns for VC investors. Careers are simply too short and variant to warrant investment.

That leaves teams. As I’ve also written before, I believe the future for esports teams is aggregation. Esports teams will act just like large global strategics – they will own a team in almost every esport, and when they cannot organically support a team they will acquire one. As a result, there will only be a limited number of teams with hands in every cookie jar.

I imagine a world similar to if Real Madrid owned soccer, American football, NBA, and hockey teams. This is only possible in esports because teams are relatively cheap to acquire at the moment and there are network effects to aggregating teams.

Just like in traditional sports, fan bases also follow power-law curve distributions. The best players will want to play for the conglomerate-type teams because they have the most money, infrastructure, and ancillary benefits. The fanbases of these teams will compound until it doesn’t make economic sense to sponsor anyone else.

Eventually, smaller teams will be bought out until only large ones remain. This is already happening – Team Solomid (TSM) and Cloud 9 (C9) have 6 and 14 team rosters respectively. Immortals Gaming Club, whose investors include Meg Whitman and Steve Kaplan, recently acquired Optic Gaming in a deal valued at $100 million.

This trend will only continue. As teams grow in size and importance, so will their bargaining power. As I mentioned previously, game producers and distributors currently earn a disproportionate amount of the gaming revenue.

Esports leagues operate as the most efficient form of marketing and advertisement for games. Without the popularity of top players and a high level of competition, this marketing would be far less effective and would reduce the stickiness of top games.

Eventually, teams will extract a fair portion of proceeds through profit sharing and other mechanisms.

Timing is Everything

Generally speaking, the earlier you enter an expanding market the better. Esports isn’t just expanding, it’s exploding. 200m+ gamers play Fortnite, League of Legends, DotA, etc. for an average of 40 hours a month. Over 700m+ people worldwide consume video game content on a monthly basis.

I believe that we are at an inflection point of technology and public perception that will allow esports to thrive. The rise of esports will affect a generational and lasting change. This is great not only for gamers, but also investors in the space. If you don’t believe my analysis, maybe peer pressure will work.

This generational shift will only accelerate with time. However, it’s still a relatively nascent industry. You only get one chance at being first.

And you won’t even be first. The earliest VC investor I could find online was Stephen Hays at Deep Space Ventures. It seems that the fund was shut down, but I really liked Stephen’s content on Hackernoon regarding esports.

More recently, Sapphire Ventures created Sapphire Sport, a $115m investment platform for technology companies at the intersection of sport, media, and entertainment. I would be shocked if they don’t make esports investments.

Finally, and perhaps most relevantly, Stephanie Zhan of Sequoia Capital has invested in 100 Thieves (100T). Like TSM and C9, 100T has multiple teams, five in fact. I was particularly excited to see Sequoia’s investment because I think their experience building businesses could help 100T truly succeed.

Esports exists in an in-between realm – it mixes elements of technology, video, sports, and social interaction. There are many merits to VC investment, but one of the valley’s defining qualities is the ability to create a new industry from preexisting pieces. That’s why I think VC funds are perfectly positioned to help esports teams reach scale.

There are moonshots, and there are loonshots. This is the former.

Hopefully you have enjoyed reading this blog post and are a little more convinced investing in esports is a worthy endeavor. If you or anyone you know is working/investing in this space, I would love to chat. I can be reached at nicktchua@gmail.com.