Take a guess on what the is most valuable form of entertainment. Is it the music industry, with Arianna Grande breaking every record? Or is it the movie industry with Endgame smashing worldwide records? It seems like everyone was talking about Game of Thrones, is it television?

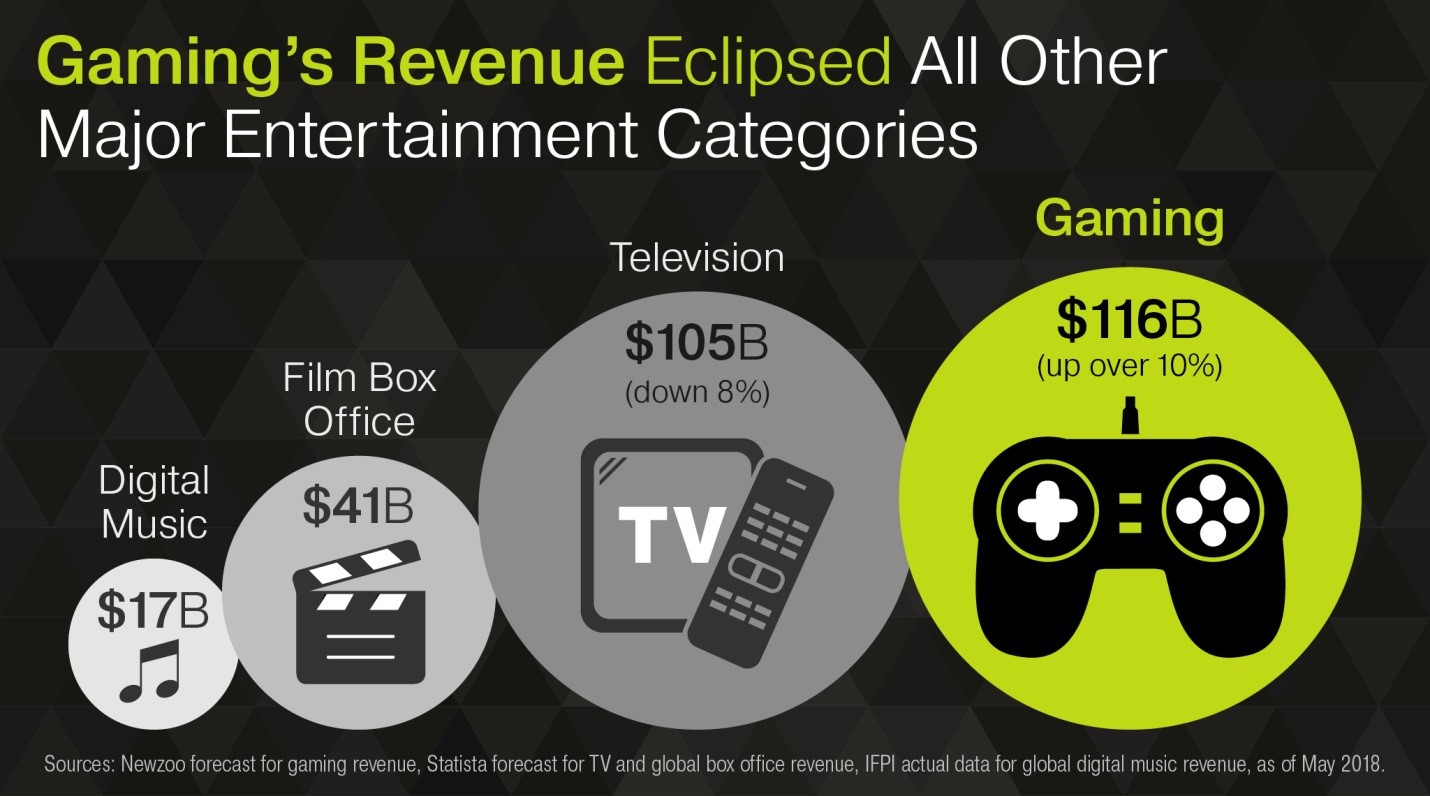

The simple answer is no, and it’s actually not even that close. Statistically the most popular and profitable form of entertainment is gaming. And it’s growing faster. Check out the graph below:

Part three of my four part position paper explores the economic forces that will drive the growth of esports. To read the first and second parts click here and here.

Video games make more than twice the music and movie industry combined, and the second highest category, television, is down while gaming is exploding. This might be surprising to a lot of people, whose first guess probably wasn’t video games. The biggest culprit is likely the lack of marketing dollars spent on gaming, while Avengers: Infinity War spent more than $150 million on TV ads alone.

When we think of the most popular type of entertainment, we probably think of what segment of entertainment spends the most on marketing. After all, our brains naturally most easily remember something we’ve seen or experienced recently. So if video games are such a big deal, why don’t we see more marketing related to gaming?

It’s because video games operate in what I call active entertainment.

Passive entertainment is any form of entertainment where our actions have no effect on the outcome. Watching TV or listening to music would qualify as passive entertainment. Attending a concert, I would argue, is active entertainment because our energy and actions at the concert influence the outcome of the concert for ourselves and others.

Advertising has no place in an active entertainment environment. Imagine pausing a concert for two minutes to run a Coca Cola ad - it just doesn’t work. On the other hand, we are accustomed to regular interruptions in passive entertainment environments, whether it be commericals on TV or ads on Pandora. But when someone is actively involved in an event, disrupting it for advertisements is the best way to ruin the experience.

Therefore, while video games may be the most prolific form of entertainment in terms of revenue, they have by and large escaped advertisements. Video games used to be paid for, and gamers definitely don’t want to be disrupted while playing.

The introduction of streaming and replay platforms like Twitch and Youtube are changing this dynamic. Suddenly gaming can be consumed passively, so there is room for advertising. When I talked to Bob Jeffrey, who ran one of the world’s best-known marketing brands J. Walter Thompson, I learned that one of the hardest-to-reach demographics is precisely the individuals who use these platforms. They are the cord-cutters, the Adblock users, and the ones who are the most comfortable buying things online. They are also the most valuable group to market to.

So what does this mean for gaming and esports in particular?

It means that there are mililions of hard-to-reach eyes available for minimal marketing spend. Remember, nascent industries like esports cannot negotiate rates with the same leverage that traditional sports networks and teams can.

For a while, however, it was hard to tell if there was a clear path to a positive ROI for advertising companies. There were two key issues that they needed to get comfortable with:

- The long-term survivability prospects of the teams and players

- The infrastructure of esports leagues as a whole

For a long time in western esports, it was very hard to know how long a team or player would stay relevant. Take Moscow Five. They were one of the more innovative organizations of their time because they consolidated teams from different esports–including Counter Strike, WarCraft, FIFA, DotA, and League of Legends–under one banner.

To put the significance of that in context, there are many venture-backed esports teams today that only own a team in one game. Granted, teams are more expensive to found or purchase now, but Moscow Five had the vision to expand beyond a chosen game. Not only did they have many teams, they had some of the best teams. Moscow Five’s League of Legends team was widely considered one of the top three teams in the world in season 2 and season 3.

So where are they today?

Nowhere. They’re gone. Some of the players rebranded into a team called Gambit, but the organization that once owned five teams disappeared in less than a year. It turns out that even if you were successful there wasn’t a lot of money in esports. Instead, their owners turned to crime to supplement their income. One of the owners was arrested in 2012 and charged with the ‘largest hacking and data breach scheme ever prosecuted in the United States’. Not a great look for the company from a marketing perspective. The money dried up after the arrest and the teams disbanded.

Many players’ were equally short for a variety of reasons. Because playing video games does include many transferable skills, the opportunity cost of attempting to play professionally is very high. Players lose time they could have spent in college or starting a career, and it’s generally harder to find a lower level job at a later age. These factors, combined with relatively low pay for even successful pros, made the average gaming career very short.

It is no wonder that companies were wary of spending marketing dollars on teams and players with short lifespans. In turn, this exacerbated the issues underlying the short careers, creating a vicious cycle. A catalyst was required to break out of the cycle.

In League of Legends that catalyst came in the form of player salaries. Riot Games, the developer behind League of Legends, realized in 2013 that they needed to provide players with salaries in order to stabilize the industry. Prior to the salaries, the primary way the teams made money was through winning prize money at tournaments. These prize pools were small to begin with, and teams that didn’t place near the top of the standings barely made anything.

In 2013 the entire landscape of the industry changed. League of Legends transitioned from a tournament-based system to a championship series similar to European soccer leagues, with established teams playing twice weekly instead of at tournaments spaced throughout the year. This stability finally allowed larger corporations to feel comfortable investing in the industry. In the same year the North American League Championship Series (NALCS) and European League Championship Series (EULCS) were formed, Riot Games received sponsorships from Coca Cola, Dr. Pepper, Red Bull, Doritos, and Qualcomm.

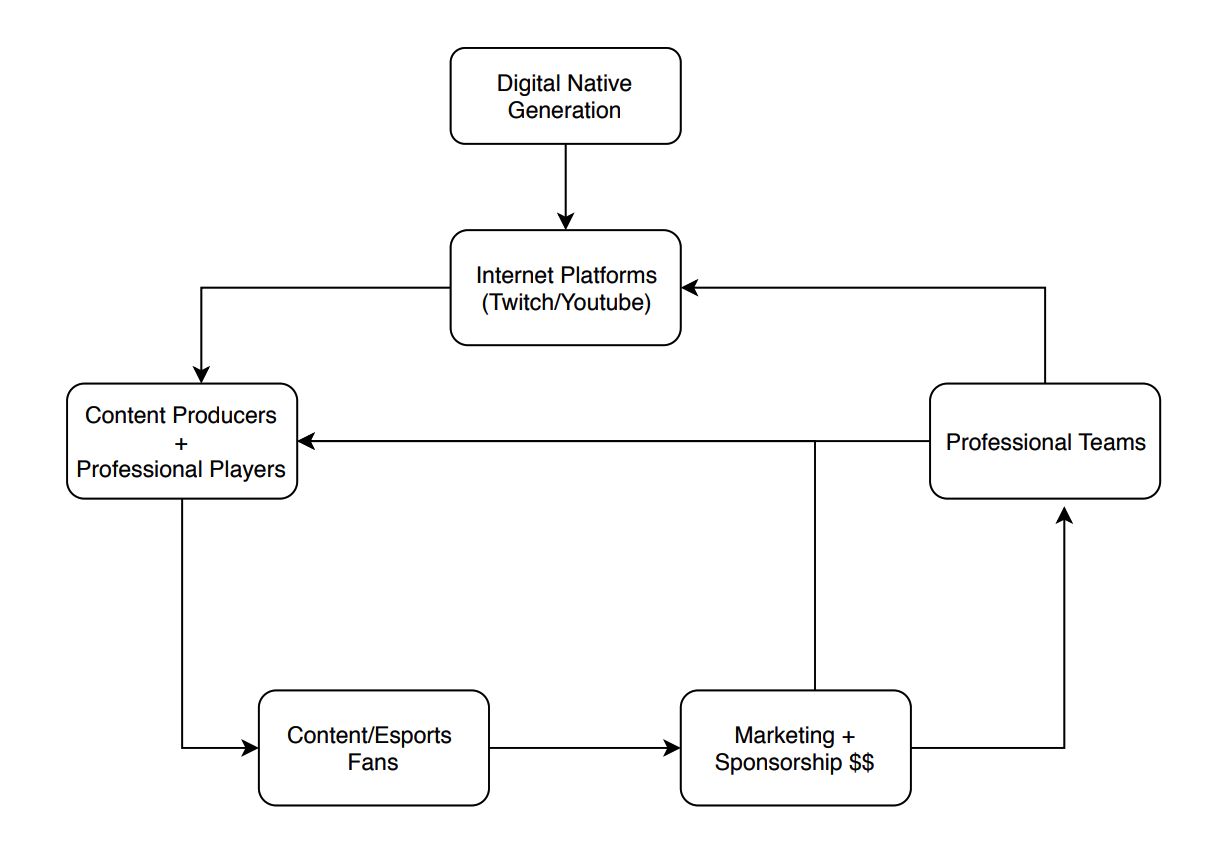

Finally, esports entered the virtuous cycle I diagrammed in my last section.

The platforms allowed content creators and professional players to generate fans, which in turn brought in marketing dollars. These marketing dollars fueled professional teams and the creators, who used the additional capital to better their content. This virtuous cycle has led more and more people to esports. Take at some of the following statistics.

- World Series viewership: 14.3 million

- NBA Finals viewership: 17.7 million

- Super Bowl viewership: 98.2 million

- LoL World Championship Finals Viewership: 200+ million

As viewers have flocked to watch League, so have sponsors. Mastercard, Kia, and Nike are now major sponsors globally. The Chinese league will now be supplied with Nike apparel in a deal similar to the NBA and NFL. State Farm sponsors the North American analyst desk just like American Express sponsors the NBA analyst desks.

It’s no surprise that there is more interest than ever in owning an esports team. League of Legends franchised the NALCS and EULCS in 2017 and 2018 respectively. Franchising a league means that they operate like the NBA or NFL. Unlike in European Soccer Leagues (which the old NALCS and EULCS were modeled off of), the worst-performing teams were no longer relegated out of the league. This provides additional safety for investors as they no longer have to worry about their team’s safety. Popular Activision Blizzard games such as Overwatch and Call of Duty have followed suit. Just like when Riot Games introduced player salaries, increased stability has been met with increased investment.

NALCS and EULCS franchise spots sold for $13 million, and players were guaranteed $73,000 in salary for a calendar year. Call of Duty franchise slots are selling for $25 million, which put it in line with Overwatch’s first teams being sold for $20 million. Want to see a return on investment? When the next Overwatch franchise slots were sold less than a year later, they went for $30 to $60 million each.

While these are a far cry from the billion-dollar price tags on traditional sports franchises, that doesn’t mean that they aren’t attracting the same high net worth investors. Here are some of the most famous investors in esports by category:

- Business Titans: Meg Whitman, Dan Gilbert, Mark Cuban, Robert Kraft

- Traditional Sports Teams: Golden State Warriors, Pittsburgh Steelers, Manchester City

- Large Companies: Disney, SAP, PayPal, Facebook, Mastercard, Nike

- Athletes: Michael Jordan, Stephen Curry, Steve Young

- Personalities: Drake, Diddy, Steve Aoki, Tony Robbins

These are just a few of the names of those now involved. Beyond just the dollar value invested, the involvement of such successful individuals and companies have changed the expectations for the industry. No longer are teams part of the wild west of esports, they either professionalize or they get replaced.

Noah Whinston is a bonafide success in esports. He founded the company Immortals while a student at Northwestern in 2015 (he was backed by Lionsgate Interactive Ventures president Peter Levin and minority owner of the Memphis Grizzlies Steve Kaplan) and soon had teams in League of Legends, Overwatch, and Counter Strike. Immortals recently raised $30 million in Series B funding in May, bringing on investors such as Meg Whitman and George Leiva (managing director of Oaktree Capital, an investment management fund with $128 billion assets under management). While still a large stakeholder, Noah has moved from CEO to COO to moving off of a managerial role entirely in a few months. Professional investment requires professional management.

Institutional capital waits for no one, and the successful teams are the ones who put the capital behind their goals. Take Team Liquid (TL). They were perennial contenders to be top of the table in the NALCS, but they consistently underperformed and placed fourth. Constantly memed, they seemed unable to break their curse. That is, until the money started pouring in.

aXiomatic partners purchased a majority stake in TL in 2016 and Disney announced an equity investment in aXiomatic and placed TL in their Disney Accelerator Program in 2017. Team Liquid has since partnered with Epic Games (creators of Fortnite, Gears of War, and many other games) and Niantic (publishers of Pokemon Go) and have since been flushed with cash. This influx of cash has also brought success. They now boast top Counter Strike, Dota 2, Super Smash, and League of Legends teams.

Far from their fourth place days the TL NALCS team has won the past three North American titles and are in the semifinals of the Mid Season Invitational, the LoL tournament that features the top team from every region in the world. They’ve done this by investing in their infrastructure and buying the most expensive players to play on their team. They have the most popular North American player, Doublelift, and their top laner Impact has a rumored salary of over $1 million a year. This has changed the memes from the ‘fourth place’ team to a team that’s ‘paid by Steve’ (a reference to their outrageous spending). They have a top of the line 10,000 sqft practice facility, and it seems like their spending is paying dividends.

Since Team Liquid is a privately held company, it’s hard to tell whether or not this spending has actually made them any money yet. But what is known is the legions of fans that it’s brought to the team. Fanbases revolve around franchise players and momentarily operating in the red to grow their fanbase doesn’t seem like a bad exchange.

For the esports industry, success is no longer an option. There is far too much money invested in the infrastructure of esports and the platforms are self-sustaining and growing faster than any other form of entertainment. However, there is still a social stigma regarding esports participants and fans. Those in the know realize that it’s only a matter of time before esports becomes normalized, it’s up to the rest of the world to catch up. But if I know anything it’s that money talks, and right now in esports it’s raining money.

The next and final section examines the challenges I think the esports industry faces, and what the future of esports will look like.