I have a dual purpose for writing book summaries: to serve as a reference point for my own learning, and to give you the reader an inside look to the book as you choose whether or not to purchase it. Since I am writing the notes from my perspective, I will most likely omit sections I am most familiar with or was uninterested by. However, you may find those sections to be the most riveting, so it’s obviously beneficial to read the whole book.

Scott Kupor has been on both sides of venture capital, first as an executive member of a startup then as an investor in thousands of startups. His book provides an inside look to the venture industry. He covers a lot of ground in the book, but there were a few things that stood out to me in particular.

The VC Investment Process

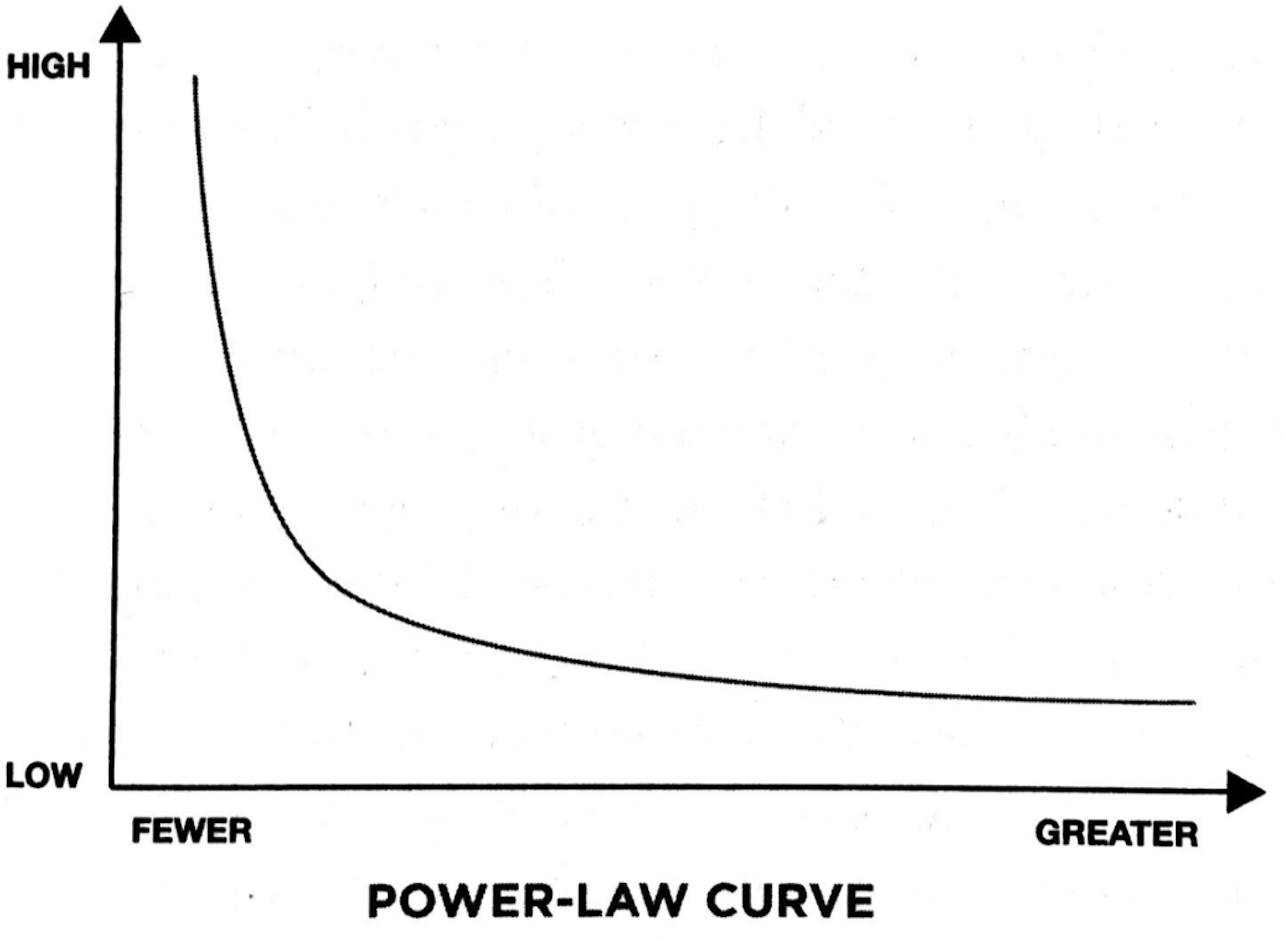

I knew before that venture capital was a game of home runs (one of the main reasons why I’m interested in it), but I didn’t realize how these home runs were aggregated by a few players. Scott describes this phenomenon as power-law returns – a small percentage of firms capture a large percentage of returns in the industry.

I’ve written about this previously through the lens of esports, but I’ve attached the graph of power-law returns if you’re a visual learner.

Scott says VCs analyze three things when evaluating an investment: people and team, product, and market. What surprised me most was his description of successful founders, “an individual needed to be so confident in her abilities to succeed that she would border on being so self-absorbed to be truly egomaniacal.”

This seems to be a common belief in venture, or at least in a16z. Ben Horowitz reiterated this idea in his 2015 commencement speech at Columbia University when he told the graduates that you cannot create value by doing what everyone thinks is a good idea. If everyone agrees, it’s likely that one of the big companies will create it and it will be business as usual.

You only create value by doing something you truly believe in that everyone else disagrees with. But you have to be right.

That’s a big caveat. But it’s empowering to know that strongly held contrarian beliefs can be valuable. It’s easy to bow to peer pressure or believe something if everyone else does, but understanding and trusting my gut instinct is something I’ll value more heavily in the future.

Next Parts

The next parts of the book talked about GPs (General Partners) and LPs (Limited Partners). This is an extremely important part of venture and it makes sense that he spent a lot of time covering, but I’m pretty familiar with the relationship due to my work with private equity.

If you’re interested in venture but not working in PE or investment banking, I’d encourage you to read this section. However, I’m skipping it for my thoughts/reactions.

Forming Your Startup:

When starting a company, there are many different options. It would be pretty exhausting to try to go over the legal ramifications of each, but Scott cuts out the middle man and says all startups should be C Corporations (C Corp).

There are a variety of reasons, most of which are tax related. If taxes bore you and you’re not going to be a founder, feel free to skip this section.

- Corporations allow for different classes of shareholders with different rights. This is important for VCs because they like to hold what are called ‘preferred stock’ while employees generally hold ‘common stock’. There’s a lot of nuances between the two which I encourage you to look up separately.

- LPs (the investors in VC funds) commonly enjoy tax-free status because they’re endowments or foundations. A LLC (what you would probably use if not a C Corp) is a ‘pass-through entity’. Pass-through entities are great because they avoid double taxation for cash flow, but they also pass tax liability to members of a LLC. Tax-free LPs would not like to see this, so VCs would probably have to pass on a LLC startup.

- It’s easier to distribute equity to employees as a C Corp. LLCs have ‘members’ while C Corps have individual shares, which makes it infinitely easier to dole out equity in the C Corp case. This is important because equity is often used to incent employees at startups.

The remainder of the section deals with option vesting, option pools, and IPO delays. That was not new or particularly interesting information to me so I won’t cover it, but I want you to know it’s in there if it interests you.

The Art of the Pitch

The next section I think was valuable because Scott confirms that you need people in the know to vouch for you, or else the chances of you getting funding are quite slim. VCs eschew the normal job listing/application processes and rely on seed/angel investors and lawyers for warm introductions.

If you’re not a crafty enough CEO to find those introductions, the thinking is you aren’t the right founder to back. Ouch.

Once you get the warm intro, he outlines five elements of the pitch.

- Market Sizing – the market might not be defined yet, but you better make sure the one you’re pitching is a big one (remember they’re trying to invest in whales!) and you have the evidence to back it up

- Team – you need to answer the why you? Quite convincingly. VCs can only invest in one company per business space because there can only be one winner in a winner-take-all market. By investing in two teams, VCs would be betting against themselves. So you better be the right people because ideas are only worth their execution.

- Product – you don’t need an exact perfect market fit yet, but you need to have the right process. Your decision making and thought process will help show if you’re the right people to back.

- Go-To-market – often the most overlooked portion (because it’s hard when you’re a young company) of the pitch, it’s important to have a meaningful conversation with the VCs about how you would approach going to market. At the end of the day, it’s something that you’ll have to be able to do.

- Planning for the Next Round of Fund-Raising – this is probably the most surprising part to me. This is something that Scott emphasized through the book that I never thought about. You should plan your funding size to be just enough to get you to the next milestone, and therefore the next round of funding. I guess this should have been obvious, but I never thought of sizing the amount of money that way since I’m used to cash positive business that can fund themselves.

The next few chapters deal with term sheets and board creation / governance. A lot of the information I know from serving on the board of Lev Digital, but there was a decent amount of new information as well.

It’s well worth reviewing individually so I won’t write out all the surprising / new parts here. Scott also makes the sections pretty brief so it’s better to look at the actual book. For completeness and my own sake I’ll list the parts I would review:

- Conversion/Auto-conversion

- Antidilution Provisions

- Drag Along Provisions

- Liquidation Preference (participating vs non-participating)

The final two chapters talk about what happens in a successful outcome (IPO or acquisition at a high multiple of investment) or an unsuccessful one (wind down).

They are extremely important and interesting sections, but there wasn’t much that I wanted to write in the sections to share.

That ends my summary/review of Scott Kupor’s Secrets of Sandhill Road: Venture Capital and How to Get it. I thought it was an amazing read as someone who hopes to be a founder one day. It was completely unnecessary for Scott to spend the time to write this book (doesn’t need the money, and doesn’t directly benefit him), but I think it really helps pierce the secretive veil of the Valley. It was a great book that I’d recommend to anyone.

Thanks again to Scott Kupor for taking the time to write the book, I really enjoyed it.