I used to be excited to log into Facebook (and Instagram) every day and post about what happened in my life. This joy is long gone, and I find myself hesitating to post more often than I find myself actually posting. I attempt to figure why.

I first started thinking about why my behavior on the platforms changed while listening to the audiobook The Lean Product Playbook by Dan Olsen. The book covers many topics, but it all boils down to finding Product Market Fit (PMF). PMF was first coined by Marc Andreesen in his essay The Only Thing That Matters.

PMF isn’t easily quantified, but it’s easily felt. Customers can’t get enough of the product, bankers are breaking down your door to get into the deal, and you can’t hire people fast enough to keep up with the demand. In years past, I believe Facebook found product market fit. My Facebook profile was central to my personal and online identity for years, but I have barely posted in the last few. In order to understand why this changed, it’s critical to understand how the product failed to shift with society.

A 13-year-old and Facebook

I was 13 years old when I first downloaded Facebook. I was pimply, in eighth grade, and I communicated with my friends through Gchat and email. The iPhone was yet to be released, and Razer phones were still the coolest ones on the market.

At the time Facebook was growing rapidly, but I wasn’t allowed to download it. My parents were (probably rightfully so) worried about data collection, online predators, and the permanence of online posts. Growing up in a (relatively) traditional Asian household, parental rules were law. You don’t really break rules.

My middle school hosted dances every once in a while, and we would often take pictures. Again, this was before the iPhone, so we had to take digital pictures and sync with our computers before posting them online. There was one dance where I took a picture with a girl I liked, but never saw the picture. One day at school I heard rumors that she had made it her profile picture. I tried viewing it online, but her profile was private unless you were her friend on Facebook.

I had to make a profile.

Armed with a completely fake name, I made a profile and told her to add me. This sparked years of posting: Where should I eat? Hi guys I was grounded! I think I failed my test lolol xD. My friends interacted with my posts and I with them. It felt like at least half of my real-world interactions were planned or recorded online.

To me, Facebook’s greatest strength was its ability to amplify real-world connections. Our posts made us feel closer to each other when physically apart, and it felt like the community was an additive force. As I came to learn, this isn’t something to be taken for granted.

A 23-year-old’s take on Facebook

My social media habits have changed immensely in the past decade. This change is probably partially due to growing older, but I believe it has to do with social media maturing as well. In 2008, social media was a novel concept. For the first time I was able to send my thoughts into the world and my friends could respond. In 2019, social media is a well-oiled machine.

Just like with any game with repeated turns, optimal strategies have emerged. Wanna be influencers and business learned the optimal time to post, editing apps like VSCO are valued in the billions, and algorithms have been manipulated for visibility. This maturation has created multiple new industries, but it also destroyed the very thing that caused the platforms to grow in the first place – joy.

Where social media was once a place for spontaneous interactions, it is now a place of calculation and precision. We have learned as a society that likes can be used as a proxy for social currency and judge/behave accordingly. In order to combat this mental change, we have to address the contributing factors.

The Necessary Change

I propose to create a distinction between public and personal profiles. Posts made by a personal profile would no longer have a public like counter while posts made by a public profile would stay as they are now. The next time you logged in you would be given a prompt to select whether you want your profile to be flagged a public/business profile or if you want it to be a personal one.

From there, the user wouldn’t have to do anything else. While personal profiles would no longer publicly show the number of likes for new posts, each post would still have the same like and comment buttons that exist currently. The total counter would still exist, however, but would only be visible by the poster.

Why does this fix the problems I mentioned?

I believe that people self-police their own content now for a multitude of reasons. If we as a society view likes as a social currency – which I believe we do – then we fear that a poorly performing post signals a poorly performing social life. Of course, viral posts have the opposite effect, but behavioral economics has shown that people value losses more than wins. Loss aversion is people’s tendency to avoid losses rather than acquiring equivalent gains – it’s better to avoid losing $20 than finding $20.

Evidence of loss aversion and social pressure can be seen in deleted posts and accounts known as ‘finstas’. A finsta (fake insta) is normally a second profile people create to add only their close friends. Pictures posted are often less manicured and more personal because the group following is deemed as trustworthy. The existence of finstas show that people still want to post personal content like they used to, but they aren’t comfortable doing so on their public (or semi-public) profile. Removing the public like counter removes the scorecard people are judged upon.

These changes won’t please everyone. Some people like the public counter, and influencers and businesses rely on public likes as a signaling factor that their products are popular. However, allowing people/businesses to choose how their profiles are categorized should limit the potential backlash. People that don’t like the change can opt out, but it’s very important that personal profiles are opted in. If personal accounts were not automatically opted in, then people may assume that profiles with non-public likes were not getting likes anyways which is counterproductive.

Hopefully these changes are useful and lead to a better user experience. At the end of the day the results are all hypothetical, so here are the key metrics I would use to measure if the change was actually successful.

User Engagement

Probably the most important metric measured by social media platforms, observing user engagement before and after the implementation would give us a clue to the effect. More specifically, do people engage more or less with their friends’ posts after they can no longer see the likes? Do they still like the post even if the counter is not public? Do people log in less than they used to? All of these will start to paint the picture.

User Posts

The premise of this article was social media platforms are less joyful to use because people are less comfortable posting. Therefore, measuring the change in user post activity will be one of the defining metrics of success. This is likely a metric that takes a while to see any progress because people have to adapt their behavior to the new system, so a lack of increase in the first few months is to be expected. We would expect, however, over a longer period of time that there is an increase in user posts as the social anxiety is mitigated. If there isn’t an uptick in posts over the period of a year or two years, then we may have to go back to the drawing board.

User Hesitation Posts

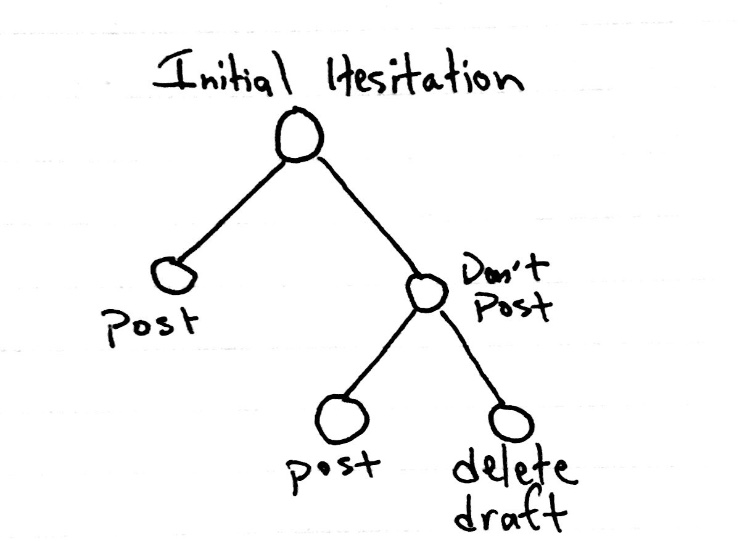

Any time a user drafted a post and paused qualifies as a user hesitation post. Facebook should (and probably does) be able to monitor when someone hesitates before posting. Any person who hesitated has a decision tree that I’ve diagrammed below.

Assuming that more posts from personal users is better for the platform, Facebook would want to increase the conversion rate from hesitation to actual posts. However, this will be mostly a short-term metric to measure (perhaps the first few months). After that, people will have adapted their behavior and the change will have less of an impact on hesitation posts.

Conclusion

I’m sure there are further tradeoffs I haven’t considered, but I believe this change will help social platforms shift from a brand-building platform to a community-driven one. A lot of the brand-building can be attributed to the gamification of likes and post engagement. By removing the most easily quantifiable and comparable metric from public view, we could limit the social pressure associated with posting. On the flip side, allowing companies/influencers to keep the metric public limits the potential disruption.

As always, ideas are only as good as their execution. This change may destroy the social media ecosystem as we know it today, but I think it’s worth a shot. I remember the days when sharing online was (mostly) uncensored and joyful. Perhaps it’s naïve to believe we could experience that feeling again, but it also seemed impossible that billions of people would be on these platforms in the first place. I’m an optimist, sue me.